Programmes

PEACE III Programme (2007 -2013)

Background

The PEACE III Programme was introduced as a distinctive Programme part-funded by the European Union (EU) through the European Structural and Investment Funds Programme (ESIF)[1]. The total value of the Programme was €333m. Of this, 67% (€225m) was provided through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). The remaining 32.5% (€108m), was provided as match-funding by the Irish Government and the Northern Ireland Executive.

Each of the PEACE Programmes aimed to build on the work of it predecessor. The economic development and seeding of civil society groups under PEACE I gave way to more focussed activities oriented towards reconciliation and cross-community contact in PEACE II. PEACE III introduced a more focused approach on reconciliation outcomes and on addressing issues of sectarianism and racism. This increased focus on reconciliation was based on the research into the meaning and definition of reconciliation that had been carried out as part of the PEACE II Programme. PEACE III also sought to introduce more streamlined delivery mechanisms.

The eligible area for the PEACE III Programme was Northern Ireland and the border counties of Ireland (Cavan, Donegal, Leitrim, Louth, Monaghan and Sligo).

Aim & Objectives

Strategic Aim: ‘to reinforce progress towards a peaceful and stable society and to promote reconciliation in Northern Ireland and the Border Region’.

Strategic Objective 1: Reconciling Communities: key activities will facilitate relationships on a cross-community and/or cross-border basis to assist in addressing issues of trust, prejudice and intolerance, and accepting commonalities and differences. In addition, key activities will seek to acknowledge and deal with the hurt, losses, trauma and suffering caused by the conflict.

Strategic Objective 2: Contributing to a Shared Society: key activities will address the physical segregation or polarisation of places and communities in Northern Ireland and the Border Region with a view to encouraging increased social and economic cross-community and cross-border engagement.

Logic Model

Programme Structure

Priorities

PEACE III carried forward the key aspects of the previous PEACE programmes, with a continued and renewed emphasis on reconciliation. It reflected discussion and research from the previous programming period around (1) defining reconciliation and (2) reviewing theories of change from peace-building literature.

PEACE III is structured to include 3 main Priorities and 5 Themes:

|

Priority |

Theme |

Overview |

|

Priority 1: Reconciling Communities |

Theme 1.1: Building positive relations at the local level – involvement of local authorities |

This Theme aims to challenge attitudes towards sectarianism and racism and to support conflict resolution and mediation at the local community level. It is to be implemented through two sub-themes. The first is the Local Authority Action Plans, which have been developed by eight local council clusters covering all of Northern Ireland, including Belfast as a single entity, and the six County Councils in the border counties. The second sub-theme is Regional Projects, which are strategic level projects implemented by Lead Partners and often with potential for impact throughout the eligible region. |

|

Theme 1.2: Acknowledging and dealing with the past – victims and survivors |

This Theme, implemented by the Consortium of the Community Relations Council and Pobal, aims to provide advice, counselling and support for victims of the conflict and their families. It also aims to exchange different views of culture, history and identity and different conflict and post-conflict experiences among relevant groups and individuals at the local level. |

|

|

Priority 2: Contributing to a Shared Society |

Theme 2.1: Creating shared public spaces |

This Theme aims to regenerate areas that have suffered as a result of the conflict and, through this, to create new opportunities for shared space and reduced segregation. |

|

Theme 2.2: Key institutional capacities are developed for a shared society |

The aim of this Theme is to develop the capacity of key institutions to deliver services that contribute to a shared society in Northern Ireland and on a cross-border basis. |

|

|

Priority 3: Programme Technical Assistance |

Theme 3.1: Technical Assistance |

Technical Assistance is used for the publicity, financial control, monitoring, evaluation, and overall management of the Programme. This Priority is implemented by SEUPB. |

PEACE III Priorities are targeted on areas and groups that have been affected by the conflict, and experience particular problems of marginalisation and isolation.

- Target areas include: sectarian interfaces; disadvantaged areas suffering the effects of conflict-related dereliction; areas that have experienced high levels of sectarian or racial problems; areas in decline due to lack of inward investment and isolated by limited cross-border linkages; areas where economic and social development has been inhibited by the conflict.

- Target groups include: victims of the conflict; displaced persons; people who have been excluded or marginalised; former members of the security and ancillary services; ex-prisoners and their families; public, private and voluntary sector organisations.

Cross-Cutting Themes

There are a number of themes relevant across all the Priorities that act as strategic guidelines for those engaged in the implementation of the Programme: These are known as ‘Cross-Cutting Themes’ and include: Cross-Border Cooperation; Equality of Opportunity; Sustainable Development; Impact on Poverty; and Partnership. As part of the project selection process, projects must demonstrate that they contribute to these themes.

PEACE III placed a strong emphasis on promoting cross-community relations and understanding. All projects were required to identify how they would address sectarian and/or racist behaviour "to enable communities to work more effectively together and demonstrate outcomes in terms of good relations and understanding".

Reconciliation Framework

To increase programme effectiveness, a significant level of simplification occurred in the development and design of PEACE III. Two key priorities were identified directly linked to an agreed definition of reconciliation and an agreed framework designed to assist in meeting Programme objectives.

The definition of Reconciliation and the Framework used was based on research carried out by Kelly & Hamber (2004) [2] as part of the PEACE II Extension Programme. Reconciliation was defined as five interwoven and related strands: (1) Developing a shared vision of an interdependent and fair society; (2) Acknowledging and dealing with the past (3) Building positive relationships (4) Significant cultural and attitudinal change (5) Substantial social, economic, and political change. The definition of Reconciliation emphasises the fundamental importance of relationships and of relationship building as part of peacebuilding and conflict resolution.

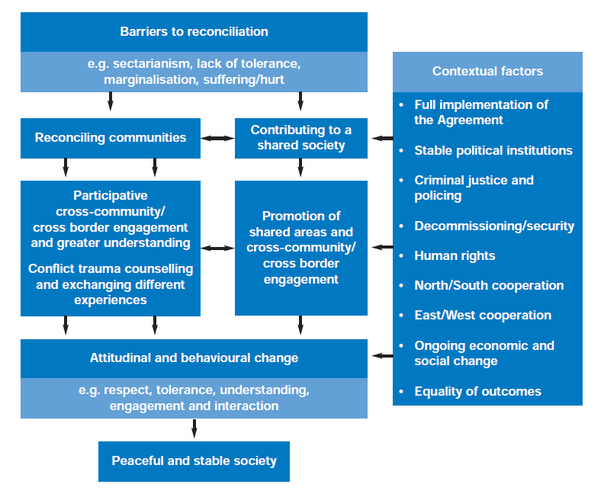

The following diagram [3] was used to illustrate this approach:

The PEACE III Operational Programme states that this framework "ensures that the Programme has adopted a greater focus on peace and reconciliation goals than under PEACE II and provides a clear distinction with the other Structural Funds Programmes".

By focusing on the two Themes of Reconciling Communities and Contributing to a Shared Society, the Programme sought to facilitate relationships and promote change. As such, the PEACE III adopted the ‘Theories of Change’ model[4]. Two theories are relevant to the problems related to the post-conflict society in Northern Ireland and the border counties and are most appropriate for changing attitudes, divisions and prejudice i.e.:

- Individual Change Theory: the basis of this theory is that peace comes through transformative change of a critical mass of individuals, their consciousness, attitudes, behaviours and skills. [Methods: investment in individual change through training, personal transformation / consciousnesses-raising workshops or processes, dialogues and encounter groups or trauma healing]; and

- Healthy Relationships and Connections Theory: the basis of this theory is that peace emerges out of a process of breaking down isolation, polarisation, division, prejudice and stereotypes between/among groups. [Methods: processes of inter-group dialogue, networking, relationship building processes, joint efforts and practical programmes on substantive problems].

The PEACE III Operational Programme outlined the transformation process required to reach the strategic aim of the Programme, as illustrated in the following diagram:

Budget

PEACE III covers the period 2007 to 2013. The end date for spend is 2015 (N+2).

|

Theme |

ERDF Budget Allocation |

Central Government Match Funding |

Total |

% of total |

|

1.1 Building positive relations |

€ 105,273,282 |

€ 64,592,158 |

€ 199,009,393 |

60% |

|

1.2 Acknowledging and dealing with the past |

€ 29,143,953 |

|||

|

2.1 Shared Space - Creating shared public spaces |

€ 67,870,586 |

€ 37,666,113 |

€ 116,049,849 |

35% |

|

2.2 Shared Society - Key institutional capacities are developed for a shared society |

€ 10,513,150 |

|||

|

3.1 Technical Assistance |

€ 12,044,678 |

€ 5,787,886 |

€ 17,832,564 |

5% |

|

TOTAL |

€ 224,845,649 |

€ 108,046,157 |

€ 332,891,806 |

100% |

Delivery Mechanisms & Processes

Programme Delivery

PEACE III projects intended to be larger scale and more strategic than in PEACE I and PEACE II with an explicit focus on building positive relationships through cross-community actions and recognition of physical segregation as an issue to be addressed. This represented a move away from the general socio-economic development focus of the previous programmes. Consequently, delivery structures changed and became significantly more streamlined in PEACE III to include two implementation bodies (SEUPB and the Consortium of CRC and Pobal), when compared to 56 implementing bodies in PEACE II and 64 in PEACE I.

The Programme management structure is summarised below:

The Accountable Department supplies the necessary public sector match funding and is accountable to its respective legislature for the totality of monies, including ERDF and match funding. These departments are listed below:

|

Priority |

Theme |

Fund |

Accountable Department |

Implementing Body |

|

|

NI |

RoI |

||||

|

Priority 1: Reconciling Communities |

Theme 1.1: |

ERDF |

OFMDFM |

DEHLG |

SEUPB |

|

Theme 1.2: |

ERDF |

OFMDFM |

DCRGA |

The Consortium |

|

|

Priority 2: Contributing to a Shared Society |

Theme 2.1: |

ERDF |

DSD |

DEHLG |

SEUPB |

|

Theme 2.2: |

ERDF |

OFMDFM |

DoF |

SEUPB |

|

|

Priority 3: Programme Technical Assistance |

Theme 3.1 |

ERDF |

DFP |

DoF |

SEUPB |

SEUPB is the Managing Authority, Certifying Authority (corporate services) and the Joint Technical Secretariat (JTS) for the PEACE III Programme. SEUPB is responsible to the European Commission, the North South Ministerial Council (NSMC), the Department of Finance (DOF) in Northern Ireland and the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (DPER) in Ireland.

A Programme Monitoring Committee (PMC) was established, chaired by SEUPB and represented by a balance of representatives and sectors. The European Commission also participated in an advisory capacity. The PMC was responsible for overseeing the Programme to ensure progress and effectiveness of implementation.

A Steering Committee was established with the remit of reviewing and selecting projects. The Committee was constituted on a cross-border basis and had technical expertise and independence to assess operations for funding. The JTS provided support to the Committee.

The Consortium: SEUPB contracted Pobal, in partnership with the Community Relations Council in Northern Ireland (‘The Consortium’) to directly deliver Theme 1.2 (Acknowledging and dealing with the past). The Consortium was an important implementing mechanism to channel support and funding to projects dealing with the legacy of the past, in particular supporting victims and survivors of the conflict. Supported projects also contributed towards building a vision of a share future. The Consortium was also commissioned by SEUPB to support and assist the local authorities in the implementation of their peace and reconciliation plans (under Theme 1.1 Building Positive Relationships at a Local Level).

Project Delivery

Lead Partners

For PEACE III, there were 220 Parent/Lead Projects (58 of which had sub-projects. In most cases these sub projects were run by different partners using an allocation of the Parent Project budget).

Creation of local partnerships / clusters

PEACE III enhanced the role of local authorities and encouraged them to group together to submit strategic bids for their areas and jointly delivered projects, in keeping with the key principle of ‘Partnership’ under PEACE III. As a result, new local government structures were established in the form of seven Peace Clusters and a standalone Belfast Peace Partnership in Northern Ireland and six County Council lead partnerships in the border counties of Ireland (i.e. a total of 14 PEACE III Partnerships). The Peace Clusters and County Council-led Partnerships were responsible for implementing Priority 1, Theme 1.

|

Lead Council (PEACE III Partnerships) |

Partner Cluster |

|

1. Belfast |

Belfast. |

|

2. Derry~Londonderry |

North West (Omagh, Strabane, Derry~Londonderry). |

|

3. North Down |

North Down, Ards, Down. |

|

4. Lisburn |

Lisburn, Castlereagh. |

|

5. Newry & Mourne |

Southern (Armagh, Craigavon, Banbridge, Newry and Mourne). |

|

6. Newtownabbey |

Newtownabbey, Antrim, Carrickfergus. |

|

7. Cookstown |

Cookstown, Magherafelt, Dungannon, Fermanagh. |

|

8. Coleraine |

North East (Ballymena, Ballymoney, Larne, Limavady, Coleraine, Moyle) |

|

9. Cavan |

|

|

10. Donegal |

|

|

11. Leitrim |

|

|

12. Louth |

|

|

13. Monaghan |

|

|

14. Sligo |

Working in partnership with communities, they developed local ‘Peace and Reconciliation Action Plans’ (a total of 28 local action plans were developed, split cross two phases i.e. Phase 1 (x14) and Phase 2 (x14)).

These partnerships enabled local people to develop and implement local action plans that promoted peace and reconciliation within their areas. The plans were innovative in developing local peace building relationships and used sports, music, arts and culture to engage local people in discussion and dialogue. Their work in addressing sectarianism and racism engaged young and old people through inter-generational projects, developed the leadership skills of local authority elected members and community leaders and delivered diversity training and awareness for the business community in a cross-border context.

The Peace Clusters and County Council-led partnerships give wide geographic reach to the PEACE Programme, which ensures that disadvantaged communities are targeted across the entire eligible area. This genuine bottom-up involvement in delivery and focus on developing skills and capacities at a local level creates a legacy of the Peace Programme and a sustainable structure for peacebuilding.

To increase the reach of the funding available through PEACE III, community and voluntary groups could access funding from Peace Clusters and County Council lead partnerships through a Small Grants Scheme.

Administration

The administration of PEACE III benefited from the reduction in the number of Implementing Bodies from 56 in PEACE II to 2 in PEACE III. This resulted in a considerable reduction in the costs of administration for the Programme. In addition, the introduction of the Lead Partner principle, which removed from smaller groups and community-based organisations the burden of bureaucracy attached to the processes of vouching, verification and reporting of expenditure, resulted in a removal of bureaucracy from smaller community-based organisations. This was based on a Small Grants Scheme administered by the Lead Partner. It resulted in freeing up resources at grassroots level to enable smaller groups to concentrate on the delivery of the projects for which they were responsible.

One of the greatest administrative challenges facing PEACE III was the length of time it was taking to process project applications, from initial application to the issuing of a Letter of Offer. This was due to the requirements for project administration to comply with the approval processes of individual government accountable departments in each jurisdiction as well as the requirements to comply with EU Structural Funds Regulations.

Monitoring and Evaluation

From the beginning, the PEACE Programmes have faced the challenge of evaluating the impact that funded projects were having on the achievement of the objectives of reconciliation and peace building. The transition from PEACE I to PEACE II reflected the experiences that had been learned in the early days of programme design and delivery by the introduction of distinctiveness criteria and in particular with the development of a clearer idea of what is meant by reconciliation as defined during the PEACE II extension. The PEACE III programme introduced for the first time the reconciliation framework agreed and developed during PEACE II into the design and structure of the Programme itself. This made it easier to identify how individual projects were contributing to the achievement of the strategic objectives of the Programme and, consequently, how they were contributing to peace-building and reconciliation.

In addition, PEACE III introduced for the first time, additional measures aimed at quantifying the specific contributions of each individual project to the achievement of the objectives of reconciliation. This was known as the Aid for Peace (AfP) approach. This approach was recommended in a report commissioned from PWC in 2007,[5] entitled ‘A Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Peace-Building.’ AfP provided a structure through which the anticipated and actual impacts of an operation on peace and reconciliation could be defined. It also assisted with the development of project-specific monitoring indicators which were used throughout the project to assess achievements against indicator targets. The downside of the approach was identified in the Mid Term Evaluation of the Programme[6] as being over-burdensome on project administrators and leading to the generation of an excessive amount of data that was difficult to evaluate, and quality assure.

Outputs & Impacts

A total of 684 applications were received for the PEACE III Programme, 220 letters of offer were accepted, and 213 projects completed across Northern Ireland and the border counties of Ireland.

|

Theme |

Number of Projects |

|

1.1: Building positive relations (Local) |

28 |

|

1.1 Building positive relations (Regional) |

61 |

|

1.2: Acknowledging and dealing with the past |

94 |

|

Priority 1 Sub Total |

183 |

|

2.1 Shared Space - Creating shared public spaces |

19 |

|

2.2 Shared Society - Key institutional capacities are developed for a shared society |

18 |

|

Priority 2 Sub Total |

37 |

|

|

220 |

|

5.1 Technical Assistance |

5 |

|

Total |

225 |

According to the Programme Closure Report (May 2016[7]), PEACE III had the following impact, based on AfP indicators:

|

PEACE III (2007– 2013) |

Outputs |

|

Number of people who attended 8,393 events that address sectarianism and racism or deal with conflict resolution. |

189,007 |

|

Number of people in receipt of trauma counselling |

6,999 |

|

Number of who attended 1,887 events assisting victims and survivors |

44,037 |

|

Number of who people attended 2,184 conflict resolution workshops. |

25,429 |

|

Number of participants from 63 interface areas engaged in initiatives which are addressing barriers (physical and non-physical) to acknowledge and deal with the past. |

2,754 |

|

Number of users of 18 shared public environments which were created or improved through cross-community regeneration projects |

136,166 |

|

Number of jobs created / safeguarded through these shared public environments created. |

117 |

|

Number of people benefited from shared services. These innovative service delivery models (at both the local and central level) directly addressed the issues of segregation, sectarianism and racism and focused on sectors such as education, community health, employability, environmental protection and sport. |

27,383 |

|

Number of pilot projects of cross-border co-operation between public sector bodies were implemented aimed at increasing the capacity for a shared society |

7 |

There was a substantial over achievement against the target number of participants for many of the activities offered through PEACE III. For example, a target of 5,000 attendees was set for events that addressed sectarianism and racism or dealt with conflict resolution. The number achieved was 70% higher at 8,393; Participants at events assisting victims and survivors were substantially surpassed with an original target of 25,000 but actual achievements of 44,037; the target number of participants from interface areas engaging in community activities was 1,090 but the number attained was 2,754; the target for trauma counselling was 5,600 individuals while the actual number achieved was almost 7,000.

Area of Impact - Community Uptake:

The degree to which the Programme benefits each of the two main communities of Northern Ireland was an important consideration in the overarching PEACE Programme. In PEACE II it was possible to demonstrate to a degree the extent to which projects were benefiting the two communities which largely used socio-economic data as the basis for demonstrating impact. However, in PEACE III many of the projects did not necessarily have an area-specific dimension.

Based on an independent Community Uptake Analysis[8] an estimated 54% of funding has been associated with the Catholic community background and 46% with the Protestant community background. Explanations for the higher level of Catholic community uptake were suggested as follows: As with PEACE I and PEACE II, there are more areas of deprivation with a Catholic majority community; and geographic factors associated with PEACE III, such as more emphasis on cross-border work and on the North West. However, in terms of applications, the analysis indicated a 48% Catholic to 52% Protestant split, which is suggested to be more reflective of the actual population.

The Implementation Review (2009)[9] discussed the potential to assess impact more deeply at a community level via the types of application and criteria being used, the types of organisations actually in receipt of funding, the type of networks being supported, and the types of community capacity being built, and consideration of decision-making processes at all levels.

The PEACE III Implementation Review (2009)[10] also highlighted that the more strategic nature of the Programme also, by design, had an important effect on the nature of successful applicants. In terms of PEACE III implementation, the evidence at that stage hinted at some difficulties within the community and voluntary sector in many areas of engaging successfully with the strategic format outside of local authority action plans.

Impact – Results from Attitudinal Surveys

An Attitudinal Survey (2014)[11] undertaken as part of the PEACE III monitoring process focused on the differences between those individuals who have participated on PEACE III initiatives compared to the wider population. It highlighted some positive messages around PEACE III including:

- CONTACT: Contact with the other community by those participating on PEACE III initiatives was much stronger than the wider population and that had improved over the PEACE III period within the participant group (90% vs 44%).

- Almost all PEACE III participants were willing to participate in cross-community and cross-border activities and the majority of participants had the opportunity to do so. In comparison, lower proportions of the wider population within the eligible region were willing to participate, especially cross-border, and fewer had such opportunities.

- CULTURE AND TRADITIONS: a higher proportion of participants (83%) felt they understand ‘a lot’ or ‘a little’ about the other Community’s culture and traditions compared with the general populations (60%).

- TRUST: A greater share of participants trust the other community. 79% of participants on PEACE III initiatives felt they could trust the other community compared to just 63% of the wider population. That level of trust has also strengthened considerable over the PEACE III period in that in 2007 just 68% of Northern Ireland participants on the PEACE programme felt that they could trust the other community. Trust by the wider Northern Ireland population has not grown to the same extent (up from 54% in 2007 to 63% in 2014/15).

- RELATIONS: Participants were more likely than the general population to give positive answers to questions about how relations between the two communities had changed over time. More participants felt relations are better than they were 5 years ago (78% vs 64%); and more participants felt relations would be better in 5 years’ time (78% vs 49%)

- ETHNIC DIVERSITY: Higher proportions of participants (76%) felt they understand ‘a lot’ or ‘a little’ about minority ethnic community cultures and traditions compared with the general populations (41%).

Theme project examples

Theme 1.1 Building Positive Relations

The 28 locally led projects focused on initiatives for building peace and reconciliation in local areas. Emphasis was placed on supporting the implementation of strategic models of collaboration between public, private and community sectors that focused on reconciliation, cultural diversity and equality. The more localised delivery structure using regional clusters resulted in a wide geographical reach as every local council area was fully involved in the PEACE programme ensuring that disadvantaged communities across the entire eligible area of Northern Ireland and the border counties were targeted. The approach developed positive relationships involving community leaders and ‘enablers/ champions’ in the development of the action plans, leading to increased buy-in, commitment and greater participation levels in activities.

The structure allowed local authorities to make inroads into addressing difficult issues around sectarianism, racism and segregation. For example, the Southern PEACE Cluster demonstrated a desire to take risks, in terms of ground-breaking work to engage with paramilitary groups and polarised communities using Community Liaison Officers. The Belfast Good Relationship Partnership, under the ‘Transforming Contested Space’ theme, demonstrated ways to reduce barriers, remove paramilitary murals and reduce inter-community tensions and conflicts in those communities at the interface. The South West Peace III Partnership supported the Speedwell Trust Initiative, which brings Catholic and Protestant primary schoolchildren together through shared activities. The Partnership funded its ‘Connecting Communities’ project, which involved school children from three different local primary schools exploring diversity in their local community with input from key local agencies including the PSNI and local churches.

The remaining 61 projects worked at a Regional and/or cross-border level with some dimension of building positive relationships addressed. They included a broad range of sectors including ex-prisoners, churches, women, rural communities, children and young people, the police, service families and cultural organisations. Projects included the Grand Lodge of Ireland ‘Stepping Towards Reconciliation in Positive Engagement’ who reported a high level of local participation in a structured programme of training and education; Co-operation Ireland’s ‘Irish Peace Centres Programme’ (€3m) which enabled four peace centres to jointly deliver innovative peace building programmes; and the FACE programme (€1m) which focused on building relationships between military service families and local communities in Northern Ireland.

Theme 1.2 Acknowledging and Dealing with the Past

This theme supported 94 projects which aimed to build on the capacity of individuals to deal with the transition to peace and reconciliation and ensure that victims and survivors of the conflict were able to deal with the past on their own terms. The theme also facilitated the exchange of different views of history, culture, identity, conflict and post conflict experiences. The theme was implemented by the Consortium of Pobal and Community Relations Council (CRC).

Projects included: INCORE’s Accounts of the Conflict in Northern Ireland (€1.1m) which created an online resource and digital repository[12] of interviews detailing a range of accounts of the conflict; The Irish Peace Process: Layers of Recollection and Meaning project[13] (€1m) created a heritage archive of one hundred interviews on the peace process and a short narrative history of the process of conflict resolution; ‘Behind the Masks’ (€381,111), a three-year training and reconciliation programme delivered by South Armagh Rural Women’s Network; and the Wave Trauma Centre ‘Back to the Future’ programme (€275,500) included, among other counselling support initiatives, a one-year training course for young people aged 18-25, which aimed to increase their knowledge and skills in the areas of trauma awareness, conflict transformation and restorative justice.

Theme 2.1 Shared Space - Creating shared public spaces

Under ‘Creating Shared Spaces’, 19 high profile regeneration projects were funded that transformed local communities. The aim was to tackle problems of separation of communities within society and address underlying issues of sectarianism, racism and prejudice by encouraging the development of physical environments that are open and welcome to all. The projects contributed to the notion of common use, interaction and engagement along with economic development in areas that have been particularly affected by conflict.

Example projects include the Peace Bridge ‘the River Foyle Foot and Cycle Bridge’ (€16.6m), The Termon Project which created new community facilities in the border villages of Pettigo and Tullyhannon (€8.1m) and with the development of Girdwood Community Hub (€10.5m) on the site of a derelict army barracks in North Belfast.

Theme 2.2 Shared Society - Key institutional capacities are developed for a shared society

This theme funded 18 projects which aimed to develop the capacity of key institutions to deliver services in a manner that contributed to a shared society across Northern Ireland and the border counties of Ireland.

Examples include the ‘FabLab’ project (€1.2m), a digital fabrication workshop split over two sites in Belfast and Derry~Londonderry, a shared space for target groups to explore and develop their creative and entrepreneurial skills in both a local and subsequently international arena; ‘BRIC – Building Relationships in Communities’ project (€3.75m) involving an innovative partnership approach the Rural Development Council (RDC), the NI Housing Executive (NIHE) and TIDES aimed promote a greater degree of sharing within the currently highly segregated social housing market and to focus on good relations, working in over 80 locations across NI from 2010 to 2014; and the ‘Planning for Spatial Reconciliation’ project (€551,346) from the Institute of Spatial and Environmental Planning (QUB) which is targeted towards the shaping of a new planning model that promotes an open, pluralist and shared society as a central feature of future legislation, policy and practice. The report, entitled ‘Making Space for Each Other: Civic Place-Making in a Divided Society'[14]recommends criteria for planners to assess whether specific plans and development schemes comply with the central goal of creating a shared and equitable society.

Project Case Studies

Examples of projects supported by PEACE III can be found by accessing the following ‘Case Study’ link

Key Programme Reports

|

Report Type |

Report Title |

|

Programme report |

|

|

Programme report |

|

|

Programme report |

|

|

Programme report |

PEACE III Equality Impact Assessment - Consultation Document |

|

Programme report |

|

|

Programme report |

|

|

Evaluation |

|

|

Evaluation |

The Story of Peace - Learning from EU PEACE Funding in Northern Ireland and the Border Region |

|

Evaluation |

|

|

Evaluation |

Building on Peace - Supporting Peace and Reconciliation after 2006 |

|

Evaluation |

|

|

Evaluation |

Implementation Analysis of PEACE III and INTERREG IVA Programmes Final Report |

|

Evaluation |

Further reports can be found by accessing the Digital Library

[1] ESIF includes money from five funds: ERDF; European Social Fund (ESF); Cohesion Fund (CF); European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD); and European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF)

[2] Kelly, G., & Hamber, B. (2004), Belfast: Democratic Dialogue, A Working Definition of Reconciliation

[4] Peter Woodrow, Strategic Analysis for Peace-building Programmes, cited by Church, C and Rogers, M. (2005) Designing for Results: Integrated Monitoring and Evaluation in Conflict Transformation Programs, Search for Common Ground, Washington.

[5] PricewaterhouseCoopers, (2006), A Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for Peace-Building (2006)

[6] SJC consultancy (formerly SJ Cartmin), (2013), Peace III Programme Mid-Term Evaluation (2013)

[7] SEUPB, (2016), PEACE III Closure Report

[8] NISRA, (May 2011), Community Uptake Analysis of PEACE III Programme, Northern Ireland’

[9] Fitzpatrick Associates, (July 2009), Implementation Analysis of PEACE III and INTERREG VA Programmes

[11] Attitudes to other communities: Comparisons between participants of the PEACE III Programme and the populations in Northern Ireland and the Border Region of Ireland, 2014/15

[12] Ulster University, International Conflict Research Institute (Incore), (n.d.), Accounts of the Conflict Digital Archive of personal accounts of the conflict in and about Northern Ireland

[13] Queen Mary University of London, Dundalk Institute of Technology and Trinity College Dublin collaboration to create The Peace Process Layers of Meaning - archive of interviews and key resources related to the peace process

[14] Gaffikin, F., Karelse, C.M., Morrissey, M., Mulholland, C., Sterrett, K.,(2016), Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, Making Space for Each Other: Civic Place-Making in a Divided Society